Collective Bargaining Through Code: How Solarpunk Fiction Imagines AI Beyond Corporate Control

A conversation with Christopher Muscato

Christopher Muscato is a historian, professor at the University of Northern Colorado, and a solarpunk fiction writer. He won a short story contest hosted by the nonprofit Fight for the Future, earning him a trip to the RightsCon conference in Taipei, Taiwan in 2025.

In this interview, we explore his perspectives on technological advancement, AI, and how he incorporates these themes into fiction, including his winning story "A Charm to Keep the Evil Eye Away from Your Campervan." We discuss his fears and hopes, how solarpunk can inspire optimism about the future, and ways communities can work together to resist corporate or state surveillance and control, and even how they can leverage decentralized and community-owned and governed technologies to adapt and survive in the ongoing climate crisis.

Editors’ note: This article is part of an expert interview series, which aims to disentangle form, function, fiction, and friction in AI systems. We invite you to inhabit the adjacent possible worldviews and engage with the conversation that follows through our call to experience it.

The Art of Paying Attention: What Drives a Climate Fiction Writer

Question: What motivates your current work? What are the values, visions, and metaphors that are driving what you’re doing today?

Christopher: Absolutely. I'm a teacher by trade, a history instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, and looking at historical precedent is crucial to how I understand our relationship with technology. Teaching has definitely influenced my view of AI. In teaching, I think that AI has become an impediment to my students’ learning, but it doesn’t have to be that way. I don't want to come across as someone who is just completely anti-technology or anti-AI in every single sense. I've written a number of fictional stories where people can use AI in ethical ways, which we can explore later. But I've seen how this technology, as it currently exists, is being rushed out as an unfinished product that is rushed out into the general populace without regard for environmental and social impacts. It's become a tool for degrading mental faculties.

Students entering my classroom are already nervous about their writing and research skills, which is understandable—I primarily teach 100-level classes, so teaching those skills is my job. Our university serves largely lower-income and first-generation college students. For them, AI looks like a tool to overcome educational challenges they fear, and I completely understand that mindset. But what it actually does is prevent them from engaging with the instruction I'm trying to provide. That’s my personal experience with AI. I understand why people see the value in it. I understand where they're coming from. I think the product, as it currently exists, is being pushed rapidly on the population and is perhaps willfully unprepared to do what it needs to do.

In my fiction, I explore technology and AI in both negative and positive lights, taking a broader view than just my classroom experience. I consider how technology, social systems, and political systems interact. The story I wrote for RightsCon focused on how fascist or fascist-leaning governments can work with corporations to integrate AI into policing, state surveillance, and population control. When examining new technology, it's crucial we consider these possibilities. It might seem hyperbolic, but one of our roles as fiction writers is to take things to their extreme so we can consider the full spectrum of the conversation we're having.

The Value of Strategic Friction: Why Resistance Points Matter

Question: “Friction” is often framed as a problem to be solved in technology design—but your contribution to the RightsCon workshop (“A charm to keep the evil eye away from your campervan”) suggests otherwise. What kinds of friction do you think are necessary or even desirable in AI systems?

Christopher: I appreciate your newsletter's point that we're not looking for friction purely for friction's sake, and I think that's similar to what we, as writers, are trying to do. When we're looking for points of friction, we are looking for organic points–places where we can understand both the appeal and the risk of technologies. When I'm writing about a technology, it's helpful to understand why people are attracted to it. If you present technology as just this big, bad, overall evil, that becomes too cyberpunk dystopian—the evil corporate overlord trope. That's a fun genre, but you do have to ask: how did we get here?

Most technologies are presented as having benefits. I mentioned that for my students, these technologies seem to help overcome insecurities about accessing education or completing part of the tasks required. In my story A Charm to Keep the Evil Eye Away from Your Campervan, the AI technologies are seen as being helpful towards resolving the climate crisis. A concept I wanted to explore in that story was “green fascism,” or authoritarian governments and corporations using the climate crisis as an excuse to push surveillance technologies onto people under the guise of environmental solutions.

The technologies in my story are meant to help people travel more efficiently—AI-driven self-driving vehicles. But they quickly become tools of corporate and state control. The "right to repair" is central to the story because these proprietary technologies force you through proprietary channels for fixes.

It's important to understand why people find technologies appealing, how they use them in daily life, and then examine the real price they’re willing to pay: What are you giving up? What are you sacrificing? How does this affect your freedom? My characters have to grapple with liking the technology and then having it turn on them.

From Luddites to Networks: Historical Lessons for Collective AI Resistance

Question: Your story also features characters collectively resisting state power, which I see as an example of a friction intervention. How do you think about the relationship between individual and collective action? How might these interventions reshape expectations for AI governance and enable people to take agency over their experiences either individually or collectively?

Christopher: Going to the RightsCon conference was incredibly beneficial. I had the opportunity to speak with people I don’t normally have access to, those working in decentralized web technologies. As a writer, talking to experts beyond my field is invaluable. I'm now expanding the story into a three-part series exploring various elements of decentralized technology.

As a historian, I turn to historical precedent to inform my fiction. When discussing AI and concepts like collectivization and collective bargaining, one of my favorite topics is the Luddites. They're often misunderstood as purely anti-technology, but that's historically inaccurate. The textile workers weren't protesting machines themselves—they were protesting how those machines exploited them. Employers used technology to produce more while paying workers less. A historian, Eric Hobsbawm, described the Luddite movement as "collective bargaining through riot." I think that framework is useful for our relationship with AI.

If we collectively choose to adopt or reject technology, not wholesale, but with specific parameters around how it's used and by whom, we can influence broader conversations and shape economic and legislative landscapes. The Luddites ultimately sought regulation protecting workers, a kind of unionization. As AI increasingly affects us all, it's important to consider what true collectivization might look like, both in real-world organizing and fiction.

I don't have all the answers - this is an ongoing conversation. But as writers, we must imagine this as expansively as possible. I'd love to see more stories, including my own, that push collective bargaining and organizing to their furthest, most radical possibilities.

I recently finished reading Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052–2072. It's not specifically about AI, but it's a powerful example of fiction exploring collectivization within our current political and economic world. Set in the near future, it explores how the climate crisis and technological risks can be mitigated through collective action.

Beyond Doomerism: Solarpunk's Role in Imagining Better Futures

Question: As a solarpunk writer, you imagine futures shaped by care, ecology, and collective survival. What is solarpunk, and what is the genre’s role at this moment?

Christopher: Solarpunk is a broad genre of climate fiction focused on achieving the most utopian outcomes possible. My quick definition: utopian, futurist climate fiction. "Utopian" means looking for the best possible outcomes, which we apply very broadly, considering how technology and marginalization factor in. "Futurist" means we're not wholesale rejecting technology, but examining ethical and responsible applications to help resolve current crises.

I really enjoy solarpunk, because it can be very easy to give in to doomerism. Doom narratives are prevalent and built into our media systems, enhanced by AI. Current AI models are heavily focused on generating clicks, shares, and visibility through largely negative output that drives engagement. Solarpunk gives us a way to step back from all that and imagine futures where we don't just doom-scroll and catastrophize, but where we actually get some things right. That's very important—to achieve anything, we have to dream it first. There can be no utopian futures without utopian imaginations that will lead us there.

That doesn't mean there won't be complications or that these are stories without conflict. It means we maintain an ultimately optimistic outlook, which drives us through them. To me, this has been tremendously helpful for navigating many conversations, and the various political, economic, and social issues we see daily in news and our personal worlds.

Nomadpunk: Mobility as Resistance to Surveillance and Control

Question: You also wrote an essay about a genre called nomadpunk - Meandering towards Nomadpunk: A Genealogy, where you talk about nomadic populations as being inspiring for their adaptability, resilience, and unpredictability. What do nomads have to do with AI? How might we use these themes to imagine frictions in AI systems?

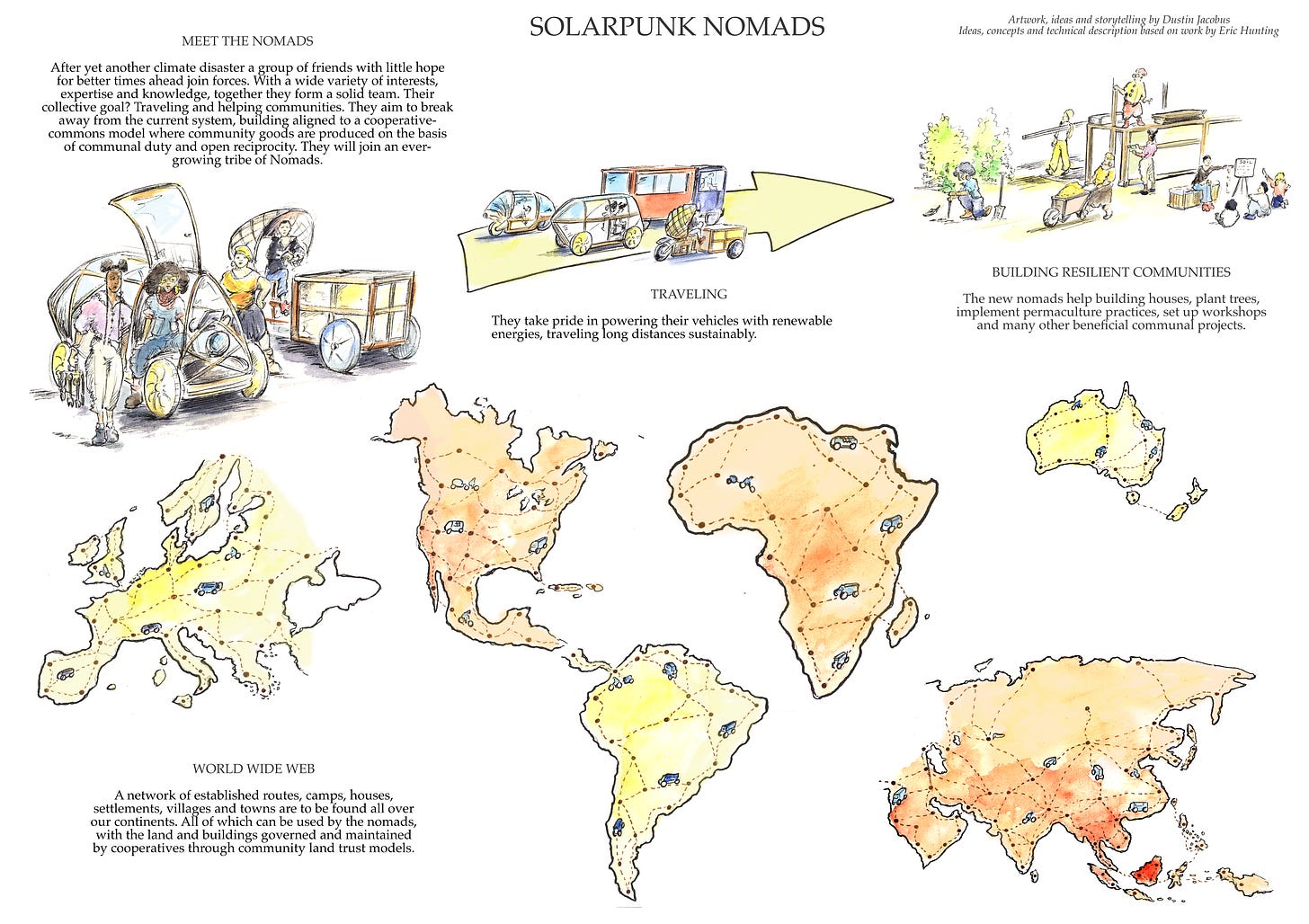

Christopher: Nomadpunk is a term I coined to describe a specific focus within solarpunk—human mobility. As I mentioned, writers need to take things to extremes to really understand them. Therefore, focusing on people whose lives are entirely based on mobility has been fascinating for engaging with concepts of surveillance, bodily control versus autonomy, borders, and restrictions.

I think we'll face pressure to resolve different aspects of the climate crisis by hunkering down and listening to state and corporate authorities—keep our heads down and do what we're told. My desire to expressly reject that is what led me to nomadpunk.

My RightsCon story featured nomads who, specifically because of their mobility, understand why surveillance systems are dangerous in ways sedentary populations don't see. This is very much an anti-border, pro-mobility idea. Corporate tyranny and political authoritarianism will likely be part of how governments deal with the climate crisis. Instead of letting governments dictate our responses, I think it's crucial we fight for autonomy and freedom of movement.

Nomadic communities succeed through high adaptability, resilience, and understanding how to interact with different weather, cultural, and economic systems. The ability to interact and move between these systems is crucial as we face increasingly uncertain times ahead. And again, as much as governments and corporations want to tell you that the best way to deal with this uncertainty is just to give more and more authority to singular figures or corporate boards, I think it's more crucial to protect our individual autonomy and community building between networks of mobile people.

The important takeaway here is that resolving these crises shouldn’t require sacrificing our personal autonomy. In fact, maintaining adaptability and resilience is vital. AI technologies can both help and hinder this. Decentralized web technologies can be fantastic for maintaining community and network-building. In my stories, characters rely on AI solutions—especially within decentralized or protected community settings—to share information like "the authorities are coming this way, so go that way," or track weather patterns. I have a whole story about a forest on treads that runs on AI, navigating the climate crisis by moving to optimal locations for weather patterns.1 The forest roams around, finding the best places to soak up the sun and avoid extreme weather events. There are many fun possibilities you can do as a writer with AI, but it's also crucial to consider the other extreme as well: who is using it and how?

Designing Tomorrow: A Vision for Community-Controlled AI

Question: If you could design one speculative friction intervention to be tested in an AI system tomorrow, what would it look like, and what would it aim to protect or challenge?

Christopher: I don't know the exact dimensions, but I'd love to see an AI system that enhances community-modeled sharing of resources and information between groups in motion together. I'm actually working—not just in fiction, but in the real world—with groups in Italy building hub stations for people wanting to become seasonally nomadic as a way to deal with the climate crisis and build resilience.

For people like that, it would be helpful to have AI systems that help them understand resource allocation. For example, AI systems that help you make sure you're using your energy most efficiently, systems that help you understand incoming weather patterns, and tools that help agriculturalists understand risks and vulnerabilities in crop systems and regulate soil microbiomes. There's a lot that can be done.

I'd like to see access to decentralized AI, ethically trained on data that isn’t stolen from copyrighted material by artists, writers, and intellectuals. AI that isn't being used to replace people from their jobs, but something that can actually be used for productive collectivization, community-building, and enhancement of networks and systems.

Access and Knowledge: The Key Differences Between Corporate and Community AI

Question: That’s truly the intention of this project: to build awareness and inspire people who are building AI to take on some of these ideas. In your stories, there is corporate AI and then other kinds of AI technological advancements that are owned by the characters themselves or their communities. What makes those different?

Christopher: The key is accessibility—both physical access and access to the knowledge base of how to use and interact with them. In my stories, where you see AI being used unethically, it's usually very restricted in accessibility. In my RightsCon story, only corporations can fix the technology—and we see this today, right? I have a cell phone, and if it breaks, I have no idea how to fix it myself, nor am I allowed to. In Taiwan, you can go to a booth in the street market, and they'll fix anything right there. But here in the United States, I have to send it to a corporate store.

In my stories, that's where we start to see AI used for control, surveillance, and authoritarianism because it's all protected and controlled. It's treated as proprietary and not something used for the collective good or knowledge. On the other hand, the nomads in my story are all about sharing collective knowledge.

What’s important is having access to decentralized technologies where you can upload your information to public services, share information, and access it. I'm not much of a technologist myself–coding and programming isn’t knowledge I have to have access to. So even if I could fix my phone and get parts myself, there's still knowledge I lack. It's important that these systems allow people to share knowledge as well as physical hardware, to tinker with code and make it more viable.

Looking at historical precedent, we see great innovation explosions when technologies are broadly available. I live in farming territory, and farmers can be marvelously innovative people. They know their fields, constantly tinker and try to fix things—that's true of people in every field. But if you have access to knowledge, tools, and time, historically, we see that technologies can flourish. The problem is that it's difficult to control, so corporations and governments don't like it. It's hard to maintain strict control over who controls new technologies.

Editors’ note and a call to experience

We’d love to hear from you! Please share your reflections in the comments here. We invite you to respond to our call to experience alternative possible futures for articulating, negotiating, and transforming friction between people and AI systems. How might Solarpunk and Nomadpunk visions inspire interventions that empower meaningful human agency in the design, development, use, and governance of AI systems?

The story is part of the “Sunshine Superhighway: Solar Sailings” anthology, which you can find here: https://www.jayhenge.com/solarsailings.html