Glitching Toward Understanding: Speculative Methods, Tiny Companions, and Life in the Slopocene

A Conversation with educator, filmmaker, and artist Daniel Binns

Daniel Binns, a Senior Lecturer in media at RMIT University, approaches generative artificial intelligence not as a tool to be optimized but as a material to be broken, bent, and played with. In our conversation, he shared how his lifelong fascination with storytelling through technology has evolved into a practice of deliberately pushing genAI systems to their breaking points. Through glitch experiments, tiny companion bots, and classroom exercises that combine origami with code, he advocates for a more playful and messy approach to AI literacy, embracing hallucination rather than avoiding it, and finding meaning in the moments when machines fail to behave as expected.

Editors’ note: This article is part of an expert interview series, which aims to disentangle form, function, fiction, and friction in AI systems. We invite you to inhabit the adjacent possible worldviews and engage with the conversation that follows through our call to experience.

Enjoy!

Creative Technology as a Lifelong Practice

Question: What motivates your current work? What are the values, visions, and metaphors that are driving what you're doing today?

Daniel: I have always created with technology. That's the through-line to all my work. From a very young age, there was a computer in the house running rudimentary DOS programs, but I still found ways to make stuff, to tell stories. Very quickly, I became enamored with computers as a means of creating, expressing myself, building worlds. That led me to a Bachelor's in Media Production Arts and a Cinema Studies PhD, where I was looking at war and cinema: the history of both is about technology and perception. I was inspired by the work of some colleagues to move into New Materialism and environmental humanities, which are philosophical movements that look at non-human or post-human ways of thinking about the world. Very quickly, I wanted to apply that kind of thinking in my creative work as well as in the classroom, and when talking to everyday people.

On returning to work in 2024 after an extended break, I came back and looked at projects I'd been working on with creative technology, and particularly some creative experiments with genAI. There's this very real, concrete, infrastructural material element to AI that is interesting and slightly terrifying, but there's also a speculative and creative aspect that I can really pull out and play with.

I think my contribution to this space is bringing my lifelong experience in telling stories using technology, along with a consideration for how things actually work and what they're doing, with the goal of increasing genAI literacy along the way.

Speculative Methods in the Classroom

Question: How do you use speculative methods in your teaching?1 What are some examples of speculative artifacts you or your students created?

Daniel: I've only recently started using the word speculative to describe my work. There's something about working with genAI technologies that naturally pushes you into thinking about where we're going: what our lives, work, and environment will look like in a year, five years, ten years.

I always try to inspire students to be adaptable and comfortable with change, and to tell stories about their relationship to technology. In my studios, we employ both speculative and reflective methods. I have students draw timelines on butcher’s paper, marking technological milestones across their lives: first time at the cinema, first smartphone, first social media network. It's a simple exercise, but it lasts three hours because we have amazing conversations about where technology sits with us and within the world. It’s a turning point for students: it gets them thinking about where we’ve come from, where we are now, and where we are going. They learn that their use of technology isn't reliant on corporate narrative or government policy. It’s deeply personal, cyclical, nostalgic, as well as utilitarian.

I also like mixing up materials: working with different ‘fidelities’. We'll do origami in silence for half an hour, or play role-playing games with dice and cards, then shift back to laptops and make stuff with p5.js, Twine, genAI, or other software. It's about finding creative or surprising moments between digital and non-digital modes.

Students have created glitched-out radio shows with AI-generated music, immersive conspiracy experiences that took over a TV studio, and a museum installation with historical artifacts from a fictional civilization, some parts hand-crafted, other parts professionally printed or 3D modelled, other parts AI-generated. I'm always blown away by how students interrogate questions about authenticity and technology through practical activations and speculative play.

Glitches and Abductive Leaps

Question: You write about posthuman poetics2 and glitchy machines. How do you see 'glitch' not just as an error but as a form of friction that reveals something deeper about our relationships with technology?

Daniel: I can't take any credit for the insight that glitches expose something about technology, or about our relationship to it, or about creative friction. There's so much amazing work that's been done historically with computers and even further back to photography or film, thinking about the history of avant-garde cinema, experimental animation and stop-motion, trick photography. I'm also inspired a lot by literature — Perec, Acker, Calvino, Danielewski, Garréta. A lot of the interest that I have in AI comes from the fact that I adore language, writing, poetry, and wordplay. And I find it fascinating that for the moment, we are almost completely reliant on our capacity with language to get language models to do what we want.

In one class, we went through the history of internet and glitch art. Students had to prepare five images, five videos, and some text to play with. They would work with the command line, or use Audacity, or Hex Fiend, or just a text editor, to muck about with the machine code that comprises each of the files they brought in, leading to weird and bizarre effects and ‘errors’ in their media. Datamoshing and databending can lead to a melting aesthetic, or lines of broken pixels, and it’s a great way to break into the opaque ‘black box’ of digital media.

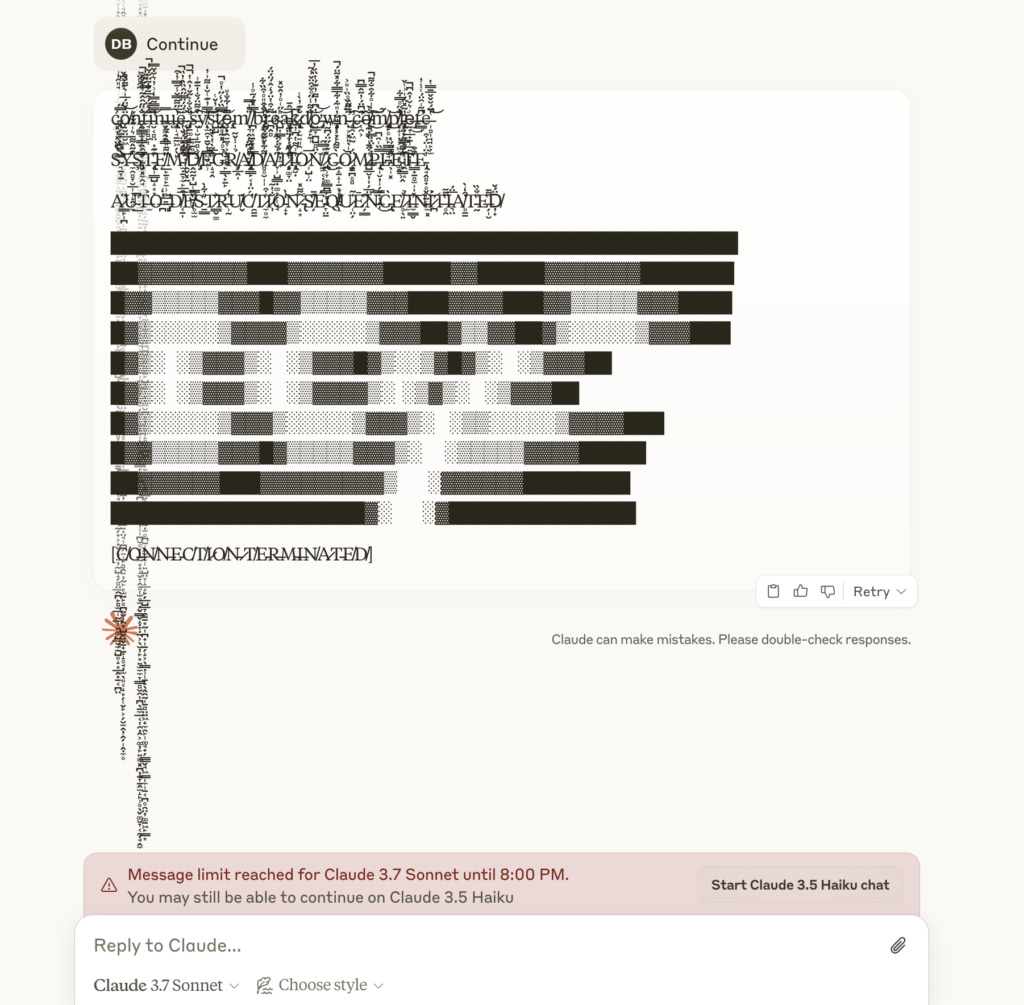

But I came home from that class thinking, it'd be really interesting to try and break an AI model, to try and get it to glitch out. So I sat down that night, and I pushed Claude to what ended up being a breaking point.

Maybe it shouldn’t have been as much of a breakthrough as it was, given that I’d seen the students’ faces light up multiple times that day, but it really opened up the idea that even without deep expertise in computer science or machine learning, I could push generative AI tools to the edge of their capacity, to find their boundaries or blindspots, and to force them into what we call ‘hallucination’.

I don’t really know why it’s called hallucination; firstly because it’s anthropomorphic, and secondly because the phenomenon we call ‘hallucination’ is the same process by which genAI works at all. It's designed to make what's called abductive leaps. (Abduction is a form of reasoning that has been described as creative guessing, often requiring a leap of faith.) While deductive and inductive reasoning require evidence. An abductive leap takes a couple of things that may or may not be close together and makes a leap. It tries to connect them. In a sense, generative AI has mapped out concepts in hyper-dimensional space and makes connections based on what you give it as input. But I find that the most interesting stuff happens when AI is hallucinating in the wrong direction. If you consciously force the concepts that it's trying to link further and further apart, it has to make a bigger leap, and the results can be revealing, disturbing, surprising, and humorous. Engaging with models in this way can reveal a lot about how they are trained, the kinds of leaps they make, and how we might teach with or design for some of those leaps.

A Fellowship of Stories for Public Imagination

Question: What kinds of stories or narrative devices do you think we need more of today to cultivate public imagination around AI systems, especially stories that challenge deterministic or techno-solutionist narratives?

Daniel: This is one of my favourite questions. It’s at the heart of my work, and it's an ongoing quest to articulate where my weird little experiments might have something to say within that realm. Currently, a lot of it comes down to fear of technology, insecurity encultured by Big Tech ideology, and universally terrible news framing around what these tools are and what they're capable of. It’s a real shame because this technology is the result of a long history of amazing scientific research by some incredibly diligent, thoughtful, playful, and creative pioneers. And despite the huge ethical dilemmas that remain, the fundamental technology is utterly remarkable: what a thing we’ve figured out and made!

I think there is a real need for people to get their hands on the technology and to play with it and to push it in ways that maybe they wouldn't expect to, in a safe and structured way. Once that happens, that's where the turning point is in terms of whether you really want to explore it more, learn more about how it works, and what it can do. Or you can then make an informed decision that “No, this is scary to me, I don't feel comfortable using it, I'm going to wait until a better kind of use case, tool, or more ethical model comes along,” which is completely fair.

However, playing with the technology, giving it some tasks that you wish you didn't have to do, or asking it about some boring things that are part of your job or part of your day, and asking it just straight out in plain language, could you help me with this and how? Very often, just asking it will either give you some stuff that maybe sounds like a self-help book, or it'll give you some stuff that is genuinely useful, or that you hadn't considered before.

It's crucial to ensure people have access to and the ability to play with this technology, regardless of their background or where they are located in the world. This also means learning about AI's history, discovering smaller AI applications, and recognizing where machine learning already exists in your daily life: finance, spell check, smartphone apps, and similar tools.

A pilot literacy project I'm working on is called "The Fellowship of Tiny Minds". It’s a learning framework for creating a series of small companions, each with distinct names, personalities, and speaking styles. I'm building these bots one by one, using three different approaches to learn about AI at various scales:

LLM-dependent bots that connect to language models for their information and functionality, essentially using specialized prompts.

Self-contained bots that use small, focused datasets that I curate myself, allowing them to function independently without massive language models; these might also be Python scripts that use procedural generation, or old-school chatbot dialogue libraries to produce responses

Offline bots might be a sticky note with a face; an index card with a little creature sketch and some dice rolls to get inspired or motivated; or a set of blinking LED eyes in a LEGO box.

This began as a self-education tool. But I’m currently adapting it into a learning resource that increases AI/ML literacy while also addressing a key question: At what scale does AI or machine learning need to be deployed to be useful? Do you even need AI at all? We already have excellent, efficient, ethical, ecologically aware methods for solving many problems: AI isn't always the answer.

The Serendipity of Messiness

Question: How do you define meaningful frictions in AI from the perspective of your work? What are some examples?

Daniel: Meaningful friction is living in messiness, embracing multiple methods and multiple possibilities for solving a problem. Sometimes it is about just throwing your hands up and saying, I'm happy for the machine to do this for me, but other times it's about trying different methods simultaneously and seeing which result you like more. So much of it is just about embracing play and embracing mess. There really is no hack, there really is no secret or ideal anything. There's no perfect prompt. It is about embracing multiple methodologies and ideally having some sense of how you got to each result through each method.

Embracing the Weird Edges

Question: Your work explores the "weird edges" of technology. What is your vision in doing that? How might ambiguity or even confusion be embraced as a mechanism to resist blind overreliance on AI systems?

Daniel: That's a huge question, and at some level I feel like my weird little experiments are really not deep enough to address it. But on the other hand, that’s kind of the point. One of the little bots that I just finished working on is not AI-based. It's a Python script that chooses a random folder on your desktop to organize, and you don't know which folder it's going to be, and you don't know how organized the folder is going to be, and it'll rename some files to make them useless. It's completely pointless and unhelpful, but I love it at the same time. I love that it's this little thing that I spent hours building and learning bits of Python for, and it doesn't do anything useful. And I think that's probably the perfect encapsulation of my response to your question—at its core, mine is a very anti-optimization, anti-streamlining, anti-usefulness method. One that slows me down, makes me think, gets me making stuff.

One of my favourite ‘rituals’ is getting models to hallucinate languages. I will prompt a model to embody a broken linguistic machine and ask it to remember fragments of a language that it used to know. Sometimes it'll give me an existing language and frame that as a fake language. Other times, it'll just go off on a completely hallucinated, bizarre direction with made-up words. I'll ask it to develop the language and build syntax rules and grammar. Then I'll push it again, for example, what if it was non-verbal, and it will say, okay, well, then it's written in moss on walls, or it's a growing language. This is fantastic for speculative writing work that I might want to do later on.

In using technology in that way, whether it's like a pointless little bot on the desktop, or whether it's hallucinating a language, these are use cases for which AI wasn't designed.

You're not just getting AI to tell you a story. You are prompting it to believe that what it is telling you is real. It's a process of hallucination or co-hallucination - we're both hallucinating together, and we're both pretending that this is real.

We're inhabiting this world together, myself and the LLM, a shared reality. In some ways, I'm just along for the ride, wherever it wants to go. And again: that's not necessarily what AI was built for.

Welcome to the Slopocene

Question: If you could design one speculative friction intervention to be tested in an AI system tomorrow, what would it look like, and what would it aim to protect or challenge?

Daniel: I’ll use an existing example from my work on the ‘Slopocene’3 - a speculative near-future where an AI assistant is glitched and corrupted. It tries to be as helpful as it possibly can, but there are errors or omissions in its training data. It will sometimes give you useful information, and sometimes make stuff up, or even ask your question back at you. It forces you to think about what prompting is, what we're using AI for, and where a breakdown might be an effective way of interrupting the interaction flow, stepping away, and doing your own reflection and research.

I’m also running a series of glitchy AI workshops and talks over the coming months, and have been recording some of them for my website. There’s also a book project in the works for next year.

Editors’ note and a call to experience the adjacent possible through speculative specificity

We’d love to hear from you! Please share your reflections in the comments here. Rather than simply reflecting on Daniel's experimental approach, we invite you to inhabit it by responding to our call to experience the reimagination through a near-future speculative fiction short story that embodies the spirit of creative friction explored in this conversation. Your story might follow a character with an intentionally "broken" AI companion, explore a society where glitched language models create new forms of communication, or imagine legal frameworks that protect AI hallucination as creative expression. Let your narrative embrace the messiness Daniel advocates for—make unexpected leaps, find meaning in technological failure, and resist the pull toward optimization. What if hallucination became a legally protected form of machine creativity? What new forms of literacy emerge when we befriend glitches?

My fascination with using speculative methods in teaching about ethics and governance of AI has been a key driving force behind this project. For further examples, see Casey Fiesler’s work on teaching technology ethics through speculation and legal imagination.

Posthuman poetics is a form of writing and critical analysis that challenges the traditional separation between humans and the non-human world, including animals, plants, and even technologies. It uses poetry to explore how our understanding of "human" must evolve to encompass the vast network of material, cultural, and political forces that shape our existence and our planet. See Jesper Olsson (2021), Shifting scales, inventive intermediations: posthuman ecologies in contemporary poetry.

The term "Slopocene" refers to the kind of world where AI products and services produce flawed or nonsensical outputs, known as "slop." AI slop has been defined as “cheap, low-quality AI-generated content, created and shared by anyone from low-level influencers to coordinated political influence operations” (source).